Invasive Plants

Invasive plants have become one of the greatest threats to native ecosystems, displacing native species, altering soil and water dynamics, and disrupting the delicate balance that has existed for thousands of years. Many invasive plants were introduced intentionally as ornamental landscaping plants, forage crops, or erosion control solutions, while others arrived accidentally through global trade and human movement. Some of the most aggressive invaders in Oklahoma—like Bradford pear (Pyrus calleryana), Chinese lespedeza (Lespedeza cuneata), and Johnsongrass (Sorghum halepense)—were brought here for agriculture or landscaping before their destructive nature was fully understood. Once established, these plants spread rapidly, often outcompeting native species due to rapid reproduction, or aggressive growth habits. Many invasive species, such as Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon) and Japanese honeysuckle (Lonicera japonica), were prized for their fast growth, hardiness, and ability to cover large areas quickly, making them common choices for lawns, gardens, and roadside plantings. Unfortunately, their adaptability also makes them incredibly difficult to control once they escape cultivation.

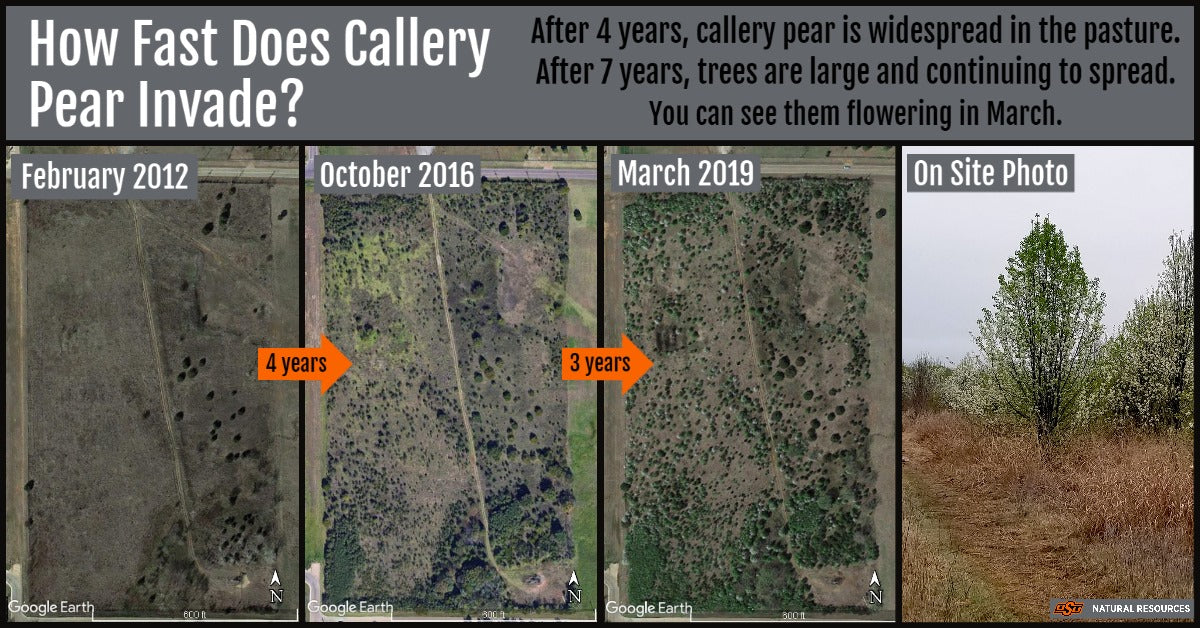

The impact of invasive plants on native species is severe. Native plants have evolved over thousands of years alongside native pollinators, herbivores, and fungi, forming a complex web of interdependence. When invasive species take over, they often disrupt these relationships, reducing habitat and food sources for wildlife. For example, Callery 'Bradford' pears, widely planted in urban areas for their fast growth and early spring blooms, have now spread into natural areas, forming dense thickets that shade out native wildflowers and grasses. Unlike native trees, they offer little benefit to pollinators or birds, turning once-diverse habitats into ecological dead zones. Similarly, Chinese lespedeza, introduced as a forage crop, has taken over grasslands and prairies, producing high levels of tannins that make it unpalatable to livestock and wildlife while preventing the growth of native grasses.

Invasive plants also alter soil chemistry and hydrology, making it harder for native species to thrive even after removal efforts. Saltcedar (Tamarix spp.), for example, not only crowds out native riparian plants but also increases soil salinity, creating conditions that favor its own growth while making it nearly impossible for native vegetation to return. Some invasive species, like Bermuda grass, create dense root systems that prevent native seeds from germinating, effectively sterilizing the ground and blocking natural plant succession.

Despite their harm, invasive plants remain common in landscaping, largely due to lack of awareness, convenience, and commercial availability. Many people still plant invasives without realizing their environmental impact because they are cheap, easy to find at garden centers, and promoted as low-maintenance solutions. Bradford pears, for instance, are still widely sold despite their tendency to become invasive, and Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense) is still used for hedges despite its aggressive spread into forests and streambanks. The continued demand for these plants, combined with insufficient regulation and control measures, allows invasive species to persist in the nursery trade and spread further into natural areas.

Once established, invasive plants are incredibly difficult and costly to remove. Many require repeated herbicide treatments, fire, or mechanical removal over several years to be fully eradicated. The best way to combat their spread is through prevention and restoration—choosing native plants instead of invasives, removing existing problem species, and restoring disturbed land with diverse, native vegetation. By making more informed choices in landscaping and land management, we can help prevent further loss of native ecosystems, protect biodiversity, and support the plants and wildlife that have thrived here for millennia.